Between 3–7pm one day in March 1968, Fa-Digi Sisòkò, a Manding-speaking bard (jeli) from West Africa, performed the epic of Sunjata—the real and semi-mythical figure who founded a vast political formation that today is often referred to as the Mali Empire.

His recitation, praise-singing and nimble plucking of his guitar was recorded by a team led by Charles Bird, an American linguist based at Indiana University.

This recording was transcribed, translated and analyzed by John William Johnson as part of PhD in folklore in the 1970s.

And this all became a book.

The Book

Actually, it became three books.

"Son-Jara: The Mande Epic (Mandenkan/English Edition with Notes and Commentary" was published in 2003 and is the third edition after those of 1986 and 1992.

It is unique because it is made up of an English translation, Johnson's scholarly commentary, and—in contrast to both the first and second edition—a transcription of Fa-Digi's performance in Manding (called "Mandenkan" in the book's title). Plus, it was initially sold with an audio CD of the performance's recording.

Published by the Indiana University Press, the hardcover book is divided into two parts:

- The Study: An extended introduction which gives dense scholarly background information about Manding-speaking society, bards and oral epics.

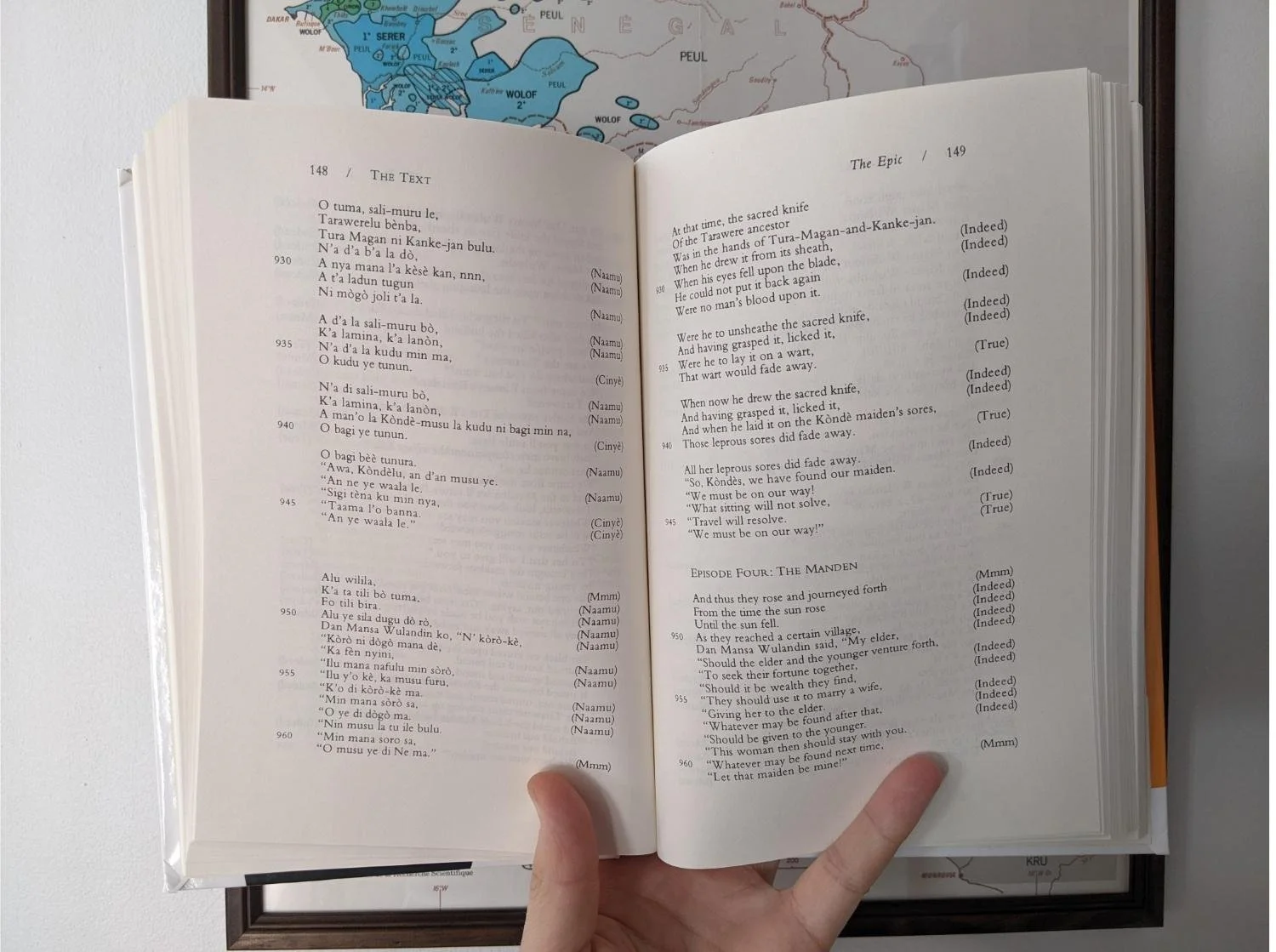

- The Text: A transcription and translation of Fa-Digi's performance with footnotes. The left page hosts the Manding and the right page, the English. Johnson's explanatory commentary is relegated to disembodied endnotes. (Unfortunately, this means that one cannot know if there is a note for a part of the text without flipping back to the endnotes on one's own.) The section is preceded by an introduction of a few pages that functions like modern-day "ReadMe" file; it shares essential information on the recorded performance and its transformation into a written text.

How to Read (and/or Listen) to the Text

The purpose of this section is to focus on the text—that is, the transcribed and translated performance of Fa-Digi Sisòkò. More specifically, I want to give students and second-language speakers of Manding, some guidance on how to read (and/or listen) to the text in its written or recorded audio formats.

Language

Fa-Digi's performance is in Manding. More specifically, it is in Maninka (commonly referred to as malinké in French), one of the four major varieties of Manding (the other being Bambara, Jula and Mandinka).

Even more specifically, it is in what the book calls "Kita Maninka". This name comes from a town in western Mali where the variety is dominant.

This distinction is important because Manding can be usefully split into two based of number of vowels: Eastern Manding varieties (with seven vowels: a, e, ɛ, i, o, ɔ, u) and Western Manding varieties with five vowels: a, e, i, o, u).

Bambara and Jula are Eastern Manding varieties. They are mutually intelligible in the same way as British and American English.

Mandinka is a Western Manding variety. It has only 5 vowels and a number of grammatical features that make it difficult to consider mutually intelligible with Bambara and Jula.

Maninka straddles the Eastern-Western division. This means that the label "Maninka" is commonly used to refer to two markedly different forms of the language:

- Eastern Maninka, which is the de facto standard found in most of southern Mali and eastern Guinea. It is largely mutually intelligible with seven-vowel Bambara and Jula as spoken in Mali, Burkina Faso and Côte d'Ivoire.

- Western Maninka, which is spoken in western Mali and smoothly bleeds into the five-vowel Mandinka of Senegal, Guinea-Bissau, the Gambia, etc.

"Kita Maninka", in short, is a form of "Western Maninka."

As such, Fa-Digi's performance presents forms of Manding that are markedly different from those that speakers and learners of Bambara, Jula, and even (Eastern) Maninka might be familiar with. (See the section below for details.)

At the same time, his speech at times is marked by other forms of Manding, most notably, Bambara. This is not surprising. The lines between Manding varieties as described above are largely idealized models created by linguistic inquiry. Speakers of the language often draw upon or move between them as different registers of a single language.

Transcription

Johnson and his team of research assistants aimed to create a transcription that was "as close to the original as possible." This means that they did not normalize the text into into written standard of Manding (e.g., Bambara or Maninka as recognized by the Malian government).

Instead, transcribers were told to write down exactly what they heard while following the spelling principles developed by Mali's Centre d'alphabétisation. (Presumably this refers to a 1968 document, "Lexique Bambara : à l'usage des centres d'alphabétisation.")

In practice, this means that the text has variable spellings that do not respect normalized Maninka or Bambara spellings of today. In some cases, this accurately reflects Fa-Digi's native variety of Manding. In other cases, it is because of unhelpfully narrow transcription. In yet others, it stems from the fact that the appropriate standard spellings had not yet been figured out.

It is also important to note the text uses the pre-1982 alphabet and spelling system that uses è, ò, ny and ng for ɛ, ɔ, ɲ and ŋ, respectively.

Formatting

The text itself is formatted in such a way as to visually represent three distinct rhythms that orally distinguish three "modes of poetry" used in the epic:

- Unindented: narrative mode

- Indented: praise-proverb mode

- Indented and italicized: song mode

Finally, the transcription includes the lines of the so-called "naamu-sayer" (naamunaamuna in Maninka) or respondent—a person (often an apprentice of the bard) that confirms or marks the end of lines with words equivalent to "Yes", "Indeed", "Alright", etc. These are marked in parentheses and the to the far right of Fa-Digi's own words.

Kita Maninka/Bambara Correspondences

If you are familiar with Bambara (or other Eastern Manding varieties like Jula or Maninka), you can easily listen to or read the text with the help of a few correspondences.

Phonology

Vowels:

e→ikilininstead ofkelen'one' (L44)tiliinstead oftele'sun; day' (L133)o→uguyainstead ofgoya'displease' (L58)dugukuluinstead ofdugukolo'earth' (L64)luninstead oflon'day' (L72)

Consonants:

linstead ofdlontaninstead ofdunan(L38)landrvarysilainstead ofsira'path' (L139)karuinstead ofkalo'moon' (L143)

Verbs and copulas

- The situative copula is

yeinstead ofbɛ. In some cases,yeis omitted. - The equative construction is

le ... diinstead ofye ... ye - The imperfective construction for verbs is

ye ... VERB-lainstead ofbɛ - The transitive perfective marker is

diinstead ofye - The intransitive perfective marker is

-daor-tainstead of-ra/la/na

Other

- Presence of

rɔ/dɔ('in') postposition, which is largely absent from Bambara - Possessive marker is

la/nainstead ofka - Plural marker is

lu/nuinstead of-w - Use of

ciɲɛinstead oftiɲɛ'truth' mun→minormum[sic] ('what')

Summary

The third edition of "Son-Jara: The Mande Epic" is a bilingual transcription and translation of a 1968 audio recording of Fa-Digi Sisòkò's performance of the epic of Sunjata. The original was performed primarily in the bard's native variety of Manding: Kita Maninka. This variety is markedly different than Bambara, Jula or (standard) Maninka (of Guinea). The trancription and (unfortunately, no-longer-available-for-purchase) recording can nonetheless be enjoyed by students of Manding if they have knowledge of a few of the major correspondences between his speech and the major Manding varieties.

[Are you interesting in studying this text? I do private lessons.]